Rakelgrava

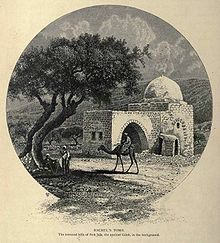

Rakelgrava (bibelsk hebraisk קבר רחל: קְבֻרַת רָחֵל Qǝbūrat Rāḥēl; moderne hebraisk; arabisk قبر راحيل: قبر راحيل Qabr Raḥīl) er ein stad som blir rekna som gravstaden til den bibelske matriarken Rakel. Staden blir òg referert til som Bilal bin Rabah-moskéen (arabisk مسجد بلال بن رباح: مسجد بلال بن رباح).[1][2] Grava blir verdsett av jødar, kristne og muslimar.[3] Ho ligg ved den nordlege inngangen til den palestinske byen Betlehem, ved sida av Rakelgrava-kontrollpunktet. Ho er bygd i stilen til ein tradisjonell maqam, arabisk for heilagdom.[4]

| Rakelgrava | |||

| |||

Rakelgrava 31°43′19″N 35°12′11″E / 31.7218998°N 35.2030554°E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Historie

endreBysantinsk tid

endreTradisjonar kring grava på denne staden kan sporast tilbake til byrjinga av 300-talet.[5] Eusebius sitt Onomastikon (skrive før 324) og Itinerarium Burdigalense (333-334) skriven av ein anonym pilgrim frå Bordeaux nemner at grava låg rundt 6 km frå Jerusalem.[6]

Tidleg muslimsk tid

endreSeint på 600-talet blei grava markert med ein steinvarde, utan nokon pynt.[6][7] På løpet av 900-talet blei ho ikkje nemnd av Muqaddasi og andre geografar, noko som tyder på at ho kan ha tapt tyding før krossfararane gjenoppliva tilbedinga.[6]

Muhammad al-Idrisi skreiv i 1154: «Halvvegs på vegen [mellom Betlehem og Jerusalem] er gravstaden til Rakel (Rahil), mor til Josef og Benjamin, dei to sønene til Jakob, fred over dei alle! Grava er dekka av tolv steinar, og over dei er ein kuppel».[8]

Benjamin av Tudela (1169-71) er den fyrste jødiske pilegrimen ein kjenner til som skildra si vitjing til grava.[9] Han nemnde ein pilar laga av 11 steinar og ein kuppel som låg oppå fire søyle, «og alle jødar som går forbi, rissar namna sine på steinane i pilaren.» Petachja frå Regensburg forklarte at dei 11 steinane representerte dei israelske stammane, utan Benjamin-stammen, sidan Rakel hadde døydd under fødselenhans. Alle var av marmor, med marmoren til Jakob på toppen.[5]

Frå rundt 1400-talet, om ikkje tidlegare, var grava under oppsyn av dei muslimske styresmaktene.[5] Den russiske diakonen Zozimos skildra henne som ein moské i 1421.[5] Ein guide frå 1467 gjev Shahin al-Dhahiri æra for å ha bygga ein kuppel, ei sisterne og ei drikkefontene på staden.[5]

Den proto-sionistiske britiske bankmannen sir Moses Montefiore vitja Rakelsgrava i lag med kona si på si fyrste vitjing til Det heilage landet i 1828.[10] Paret var barnlaust, og lady Montefiore blei djupt rørt av grava,[10] som var i god stand på den tida. Før paret vitja staden att, i 1839, hadde jordskjelvet i Galilea i 1837 gjort mykje skade på grava.[11]

I 1841 renoverte Montefiore staden og fekk nøkkelen til grava for jødane. Han renoverte heile strukturen, rekonstruerte og kvitkalka kuppelen og la til eit forkammer, inkludert ein mihrab for muslimsk bønn, for å mildna muslimsk frykt.[12]

I 1845 stod Montefiore for fleire utbetringar av bygningen.[13] Han fekk tilføydd eit nytt forkammer i aust for muslimsk bønn og gravleggingsførebuing, kanskje som ei forsonande handling.[14] Rommet hadde ein mihrab vend mot Mekka.[15][16]

I 1864 gav jødane i Bombay pengar til å grava ein brønn. Sjølv om Rakelgrava berre låg ein og ein halv time til fots frå gamlebyen i Jerusalem, blei mange pilgrimar tørste på vegen og kunne ikkje finna drikkevatn her. Kvar rosh hodesj (fyrste dagen av den jødiske månaden) førte jomfrua frå Ludmir følgjarane sine til Rakelgrava og leia ei bøneteneste med ulike rituale, som inkluderte å spreia ut bøner frå dei siste fire vekene over grava. På den tradisjonelle årsdagen for dødsfallet til Rakel førte ho ein høgtideleg prosesjon til grava der ho song salmar heile natta.[17]

I 1912 gav dei osmanske styresmaktene jødane løyve til å reparera sjølve heilagdommen, men ikkje forkammeret.[18] I 1915 hadde bygningen fire veggar, kvar av dei ca 7 m lange og 6 m høge. Domen nådde kring 3 meter.[19]

Ved den arabisk-israelske krigen i 1948 blei området okkupert og annerktert av Jordan. Våpenkvileavtalen frå 1949 garanterte i teorien fri tilgang til grava, sjølv om israelarar, som ikkje kunne koma inn i Jordan, blei hindra frå å vitja henne.[20] Jødar som ikkje var israelske heldt likevel fram med å vitja området.[21] I denne perioden blei den muslimske gravlunden utvida.[22]

Etter Seksdagarskrigen i 1967 okkuperte Israel Vestbreidda av Jordanelva, som omfattar Rakelsgrava. Grava blei underlagt israelsk militærstyre. Statsminister Levi Eshkol meinte grava måtte bli del av dei nye utvida kommunegrensene til Jerusalem,[treng kjelde] men forsvarsminister Moshe Dayan valde av tryggleiksgrunnar å ikkje omfatta henne i territoriet som blei lagt til Jerusalem.[23]

Islamske halmånar i romma i bygningen blei så fjerna. Muslimar fekk forbod mot å nytta moskéen, men fekk løyve til å nytta gravlunden ei stund til.[24] Frå 1993 fekk ikkje lenger muslimar nytta gravlunden.[24] Ifølgje Betlehem-universitetet er «tilgang til Rakelgrava no avgrensa til turistar som kjem inn frå Israel.»[25]

Oslo II-avtalen frå 28. september 1995 plasserte Rakelgrava i ein palestinsk enklave (Areal A), med ei særarrangement som gjorde henne - i lag med hovudvegen Jerusalem-Betlehem - underlagt israelsk tryggleiksansvar.[26]

1. desember 1995 blei resten av Betlehem, med gravenklaven som einaste unntak, underlagt den fulle kontrollen til dei palestinske sjølvstyresmaktene.

I 1996 byrja Israel å forsterka området i eit 18 månader langt prosjekt som kosta 2 millionar dollar. Det inkluderte ein 13 fot (4,0 m) høg mur og ein militærpost.[27]

11. september 2002 godkjente det israelske tryggleiksrådet at graven skulle leggjast inn på den israelske sida av Vestbreidda og omringa av ein betongmur og vakttårn.[26] I februar 2005 avviste den israelske høgsteretten ein palestinsk appell om å endre ruta til Vestbreiddebarrieren i området med grava.[28] Bygginga av barrieren øydela det palestinske kvarteret Qubbet Rahil (‘Rakelgrava’), som omfatta 11% av Betlehem.[29][30] Israel erklærte området som ein del av Jerusalem.[24] I 2011 blei det oppretta eit «Barrieremuseum» av palestinarar på nordveggen av den israeliske barrieren kring Rakelgrava.[31][32][33]

Replikaer

endreGrava til sir Moses Montefiore, ved Montefiore-synagogen i Ramsgate i England, er ein kopi av Rakelgrava.[34][35]

-

Gravstein i form av Rakelgrava ved Trumpeldor gravlund i Tel Aviv.

-

Montefiore-mausoleet i Ramsgate.

Kjelder

endre- ↑ Carbajosa, Ana (29 October 2010). «Holy site sparks row between Israel and UN». The Guardian. Henta 13 March 2012.

- ↑ «Israel clashes with UNESCO in row over holy sites». Haaretz. 3. november 2010. Henta 13 March 2012.

- ↑ Conder, C. R. (1877). «The Moslem Mukams». Quarterly Statement – Palestine Exploration Fund 9 (3): 89–103. doi:10.1179/peq.1877.9.3.89. «Alone and separated from the family sepulchre, the little "dome of Rachel " stands between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The Kubbeh itself is modern, and has been repaired of late years. In 700 A.D. Arculphus saw only a pyramid, which was also visited by Benjamin of Tudela in1160 A.D., and perhaps by Sanuto in 1322 A.D. The site has been disputed on account of the expression (1 Sam. x. 2) " in the border of Benjamin," and there can be no doubt that the Kubbet Rahil never was on or very near this border. The Vulgate translation, however, seems perhaps to do away with this difficulty, and as Rachel’s tomb was only “a little way” from Ephrath, "which is Bethlehem" (Gen. xxxv. 16–19), and the tradition is of great antiquity, there is no very good reason for rejecting it.»

- ↑ Conder, C. R. (1877). «The Moslem Mukams». Quarterly Statement – Palestine Exploration Fund 9 (3): 89–103. doi:10.1179/peq.1877.9.3.89. «Alone and separated from the family sepulchre, the little "dome of Rachel " stands between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The Kubbeh itself is modern, and has been repaired of late years. In 700 A.D. Arculphus saw only a pyramid, which was also visited by Benjamin of Tudela in1160 A.D., and perhaps by Sanuto in 1322 A.D. The site has been disputed on account of the expression (1 Sam. x. 2) " in the border of Benjamin," and there can be no doubt that the Kubbet Rahil never was on or very near this border. The Vulgate translation, however, seems perhaps to do away with this difficulty, and as Rachel’s tomb was only “a little way” from Ephrath, "which is Bethlehem" (Gen. xxxv. 16–19), and the tradition is of great antiquity, there is no very good reason for rejecting it.»

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 5,2 5,3 5,4 Pringle, 1998, p. 176

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 Sharon 1999.

- ↑ Edward Robinson, Eli Smith. Biblical researches in Palestine and the adjacent regions: a journal of travels in the years 1838 & 1852, Volume 1, J. Murray, 1856. p. 218.

- ↑ Le Strange 1890.

- ↑ Jewish Studies Quarterly: JSQ. Mohr (Paul Siebeck). 1994. s. 107. «Benjamin of Tudela ( 1170 C.E.) was the first Jewish pilgrim to describe his visit to Rachel's Tomb.»

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 Abigail Green (2012). Moses Montefiore. Harvard University Press. s. 67. ISBN 978-0-674-28314-5. «On the second day of their visit, Amzalak took Montefiore on a tour of communal institutions and Jewish holy places. Judith, meanwhile, set out on a day trip to Bethlehem, stopping at the Tomb of Rachel, which she visited in the company of a group of Jewish women. This desolate, solitary, crumbling ruin, its dome half open to the elements, was a holy site for all Jews. For an infertile woman like Judith it may have had special significance. The Old Testament contains many tales of barren women who were finally able to conceive through divine intervention. The matriarch Rachel was one of them. Indeed, Rachel had been so distressed by her inability to bear children that she went to her husband Jacob and complained, "Give me a child! And if there will be no child, I shall die!" Consequently, the Tomb of Rachel has become a favorite site of religious pilgrimage for infertile Jewish women. It seems strange to associate such a practice with a well-educated Englishwoman like Judith. Yet she must have been more aware of these superstitions than her published diaries indicate, because Judith was the owner of a fertility amulet-written for her by two Sephardi rabbis, whose family were the hereditary guardians of Rachel’s Tomb.»

- ↑ Strickert 2007.

- ↑ George Frederick Owen (1977). The Holy Land. Kansas City: Beacon Hill Press. s. 159. ISBN 978-0-8341-0489-1. Henta 2 January 2012. «In 1841, Sir M. Montefiore purchased the grounds and monument for the Jewish community, added an adjoining prayer vestibule, and reconditioned the entire structure with its white dome and quiet reception or prayer room.»

- ↑ Sered, Our Mother Rachel, in Arvind Sharma, Katherine K. Young (eds.). The Annual Review of Women in World Religions, Volume 4, SUNY Press, 1991, pp. 21–24. ISBN 0-7914-2967-9

- ↑ Whittingham, George Napier. The home of fadeless splendour: or, Palestine of today, Dutton, 1921. p. 314. "In 1841 Montefiore obtained for the Jews the key of the Tomb, and to conciliate Moslem susceptibility, added a square vestibule with a mihrab as a place of prayer for Moslems."

- ↑ Pringle, 1998, p. 176

- ↑ Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz. Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. ISBN 1-57607-004-2

- ↑ Nathaniel Deutsch (2003). The maiden of Ludmir: a Jewish holy woman and her world. University of California Press. s. 201. ISBN 978-0-520-23191-7. Henta 10 November 2010.

- ↑ «United Nations Conciliation Commission For Palestine: Committee on Jerusalem. (April 8, 1949)». Arkivert frå originalen June 4, 2011.

- ↑ Bromiley, Geoffrey W. The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q–Z, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995 (reprint), [1915]. p. 32. ISBN 0-8028-3784-0

- ↑ Daniel Jacobs, Shirley Eber, Francesca Silvani. Israel and the Palestinian territories, Rough Guides, 1998. p. 395. ISBN 1-85828-248-9

- ↑ Tom Selwyn. Contested Mediterranean Spaces: The Case of Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem, Palestine. Berghahn Books. s. 276–78.

- ↑ Linda Kay Davidson, David Martin Gitlitz. Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 511. ISBN 1-57607-004-2

- ↑ Benveniśtî, Mêrôn. Son of the Cypresses: Memories, Reflections, and Regrets from a Political Life, University of California Press, 2007, pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-520-23825-7

- ↑ 24,0 24,1 24,2 Tom Selwyn. Contested Mediterranean Spaces: The Case of Rachel's Tomb, Bethlehem, Palestine. Berghahn Books. s. 276–78.

- ↑ "Bethlehem University Research Project Explores Importance of Rachel's Tomb." Bethlehem University. 4 May 2009. 25 March 2012.

- ↑ 26,0 26,1 Breger, Reiter & Hammer 2013: "Rachel’s Tomb was originally assigned to Palestinian Area A under the 28 September 1995 Israel–Palestine Interim Accords and thus came under full Palestinian responsibility for internal security, public order and civil affairs. Annex I, Article 5 provided that "during the Interim Period" Israel will have security control of the road leading to the Tomb and may place guards at the Tomb. On 11 September 2002, the Israeli security cabinet approved placing Rachel's Tomb on the Jerusalem side of the Security Wall, thus placing Rachel's Tomb within the "Jerusalem Security Envelope," and de facto annexing it to Jerusalem."

- ↑ Strickert 2007, s. 135.

- ↑ Marianne Moyaert (5 August 2019). Interreligious Relations and the Negotiation of Ritual Boundaries: Explorations in Interrituality. Springer. s. 76–. ISBN 978-3-030-05701-5.

- ↑ Maria Kousis; Tom Selwyn; David Clark (1 June 2011). Contested Mediterranean Spaces: Ethnographic Essays in Honour of Charles Tilly. Berghahn Books. s. 277–. ISBN 978-0-85745-133-0.

- ↑ Marianne Moyaert (5 August 2019). Interreligious Relations and the Negotiation of Ritual Boundaries: Explorations in Interrituality. Springer. s. 76–. ISBN 978-3-030-05701-5.

- ↑ «The "Wall Museum" – Palestinian Stories on the Wall in Bethlehem Rania Murra, Toine Van Teeffelen Jerusalem Quarterly 55 (2013), pp. 93–96: "Once the area around Rachel's Tomb, a pilgrimage place for Muslims, Christians and Jews, was one of the liveliest in Bethlehem. The Hebron Road connected Jerusalem with Bethlehem: its northern section was the busiest street in town. It was the gateway from Jerusalem into Bethlehem. After entering Bethlehem along the main road, visitors either chose the direction to Hebron or the road to the Church of the Nativity. Times have changed. During the 1990s Rachel's Tomb became an Israeli military stronghold with the Jerusalem-Bethlehem checkpoint close by. As such it was a focus of Palestinian protests, especially during the Second Intifada after September 2000. In 2004–05 Israel built walls near the Tomb and a surrounding enclave, both of which it had already annexed to Jerusalem. The Tomb thus became forbidden territory to inhabitants of Bethlehem. In the course of time no less than sixty-four shops, garages, and workshops along the Hebron Road closed their doors. This was not just because of the fighting, shooting and shelling going on during the Second Intifada, but also because the area became desolate as a result of the Wall. Parents warned their children not to visit the area with its imposing 8–9 meter high concrete Wall – almost twice as high as the Berlin Wall."» (PDF).

- ↑ «Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 11 (1): 83–110» (PDF). doi:10.1515/jef-2017-0006. «The Arab Educational Institute (AEI), which is a member of the international peace movement Pax Christi, opened the Sumud Story House in 2009. The Sumud Story House is a building located in the Rachel's Tomb Area where Palestinian women from Bethlehem and the neighbouring towns gather weekly to narrate their experiences living in a walled city. These stories have been written and printed on panels posted on the Wall in the Rachel's Tomb Area constituting the Wall Museum.»

- ↑ «Maan News Agency». Maannews.com. Henta 25. februar 2019.

- ↑ Sharman Kadish, Jewish Heritage in England : An Architectural Guide, English Heritage, 2006, p. 62

- ↑ Sharman Kadish, Jewish Heritage in England : An Architectural Guide, English Heritage, 2006, p. 62

- Denne artikkelen bygger på «Rachel's Tomb» frå Wikipedia på engelsk, den 25. november 2023.